Every teacher knows how quickly students will spot when something feels unfair. A single missed consequence, a forgotten reward, or a hint of favoritism can undo weeks of careful work. In a classroom economy, fairness and consistency aren’t just helpful, they are the system’s lifeblood.

Banking tokens to keep the game clean

In this design, tokens are “in play” only for the timetable cycle, usually a week or a fortnight. At the end of the cycle, they are banked and recorded. This creates a natural reset, no one stays stuck at the bottom, and no one can coast forever at the top. Over time, those banked totals accumulate toward bigger end of term activities such as auctions.

Students quickly understand the balance, immediate reinforcement sparks motivation, while delayed reinforcement sustains commitment. It mirrors how adults work for wages that arrive weekly, while also saving toward long term goals.

The teacher’s role, consistency, not control

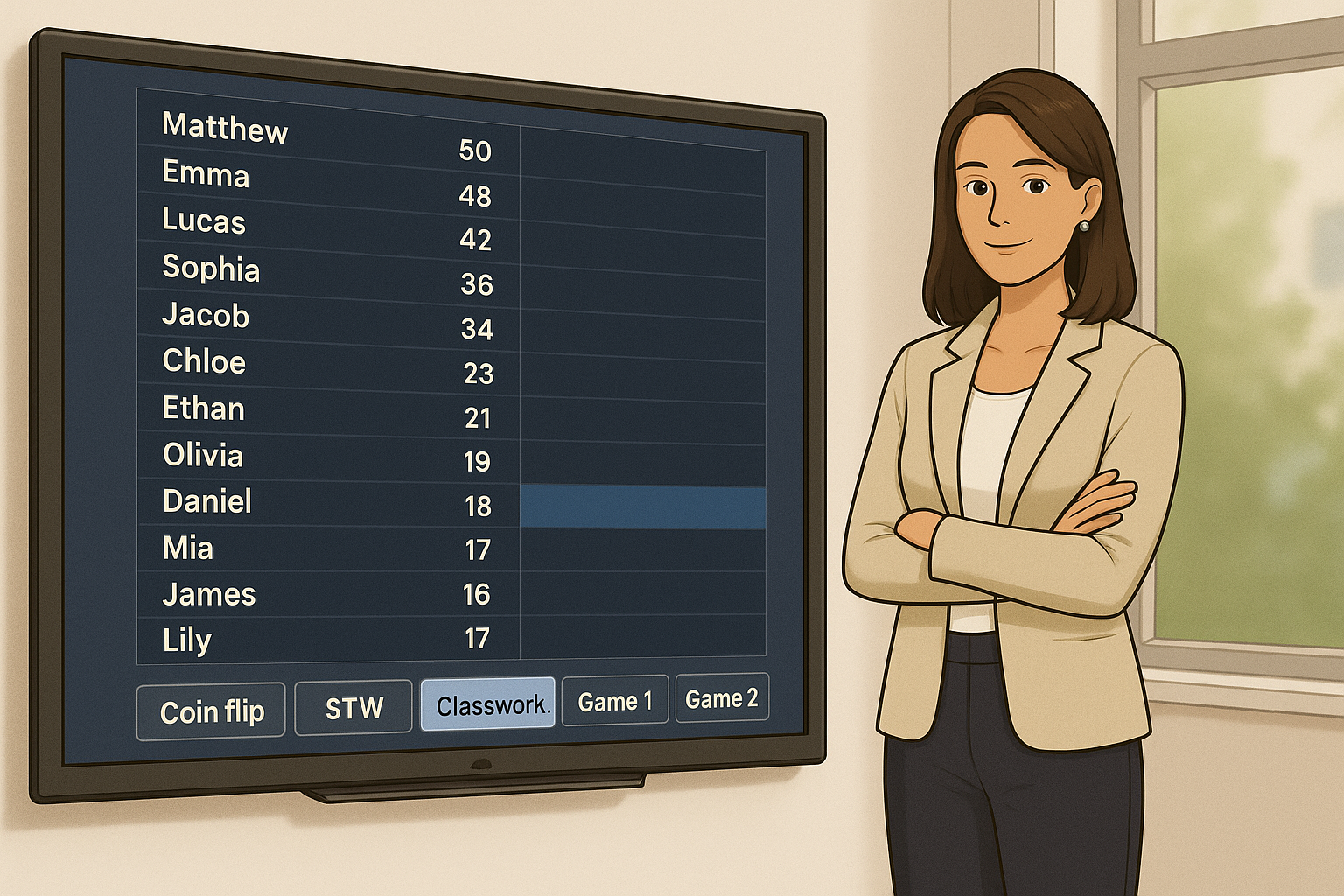

A classroom economy only works if students believe the “referee” is fair. Teachers still hold autonomy to weight points depending on lesson design (for example, more tokens for engagement during the individual classwork chapter, fewer for a warm up task). But once the rules are set, consistency is non negotiable.

- If one student is penalized for being off task, all students should expect the same.

- If tokens are awarded for a correct answer, every correct answer earns them, not just the ones the teacher notices.

- If the system includes second chances, they must apply equally.

Why fairness drives participation

Research shows people are motivated not only by rewards but also by fairness. The Ultimatum Game, first studied in 1982 by Werner Güth and colleagues, makes this clear. In the experiment, one player is given a sum of money and proposes a split with a second player. If the second player accepts, both keep the money, if they reject, neither gets anything. Rationally, any positive amount should be accepted, yet unfair offers are routinely rejected. People will sacrifice money to uphold fairness, evidence that perceived integrity can outweigh short term gain.

A classroom story

Imagine two Year 8 classes trialing the same economy. In the first, a teacher forgets to deduct a token from a student who breaks the rules. The others notice instantly. The signal is clear, the rules aren’t worth investing in. Participation drops.

In the second class, the teacher applies the rules without exception, and tokens are banked weekly so no one falls hopelessly behind. Here, the system builds its own momentum. Even students who rarely win week to week stay engaged, because they know their banked totals will matter when the auction comes.

A real world parallel

Think about taxation, people don’t just care about the rate they pay, they care whether others are paying their fair share. When they suspect corruption or inconsistent enforcement, trust erodes and compliance falls. Classroom economies rise or fall not on the size of the reward but on the integrity of the rules.

References

- Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.

- Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

- Midgley, C. (1987). The role of classroom goal structure in students’ motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology.